Visual Storytelling in 'Raiders of the Lost Ark': Response to Soderbergh's Blog

- Antony Gafarov

- Feb 13, 2024

- 9 min read

Recently, a long time friend (and supporter of the site) showed me a blog post titled Raiders by Steven Andrew Soderbergh, director of Ocean's Eleven (2001), Contagion (2011), and many more famous films. In it, Soderbergh analyzes “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981), directed by Steven Spielberg and cinematography by Douglas Slocombe, by inviting the audience to critically watch the film’s composition, movement, and editing, and simplifies the process by uploading the entire film in black and white with no sound.

Firstly, I cannot recommend highly enough reading his post and watching the edit for yourself, but I'd like to analyze a claim Soderbergh makes:

“…understanding story, character, and performance are crucial to directing well, but I operate under the theory a movie should work with the sound off, and under that theory, staging becomes paramount…” (Soderbergh, 2014)

At a surface level, I do not disagree with his claim. Efficient visual storytelling hinges on the ability to convey a scene as quickly as possible to an audience via the director’s staging, the cinematographer’s composition, and spatial-temporal editing to minimize the burden on audio; a failure in efficient visual storytelling results in an over reliance on audio narration, leading to exposition dumps. However, my education and experience in audio production made me skeptical of his theory, because he implies that Raiders of the Lost Ark is not only watchable, but hardly even requires audio to enjoyably convey the story.

It was my belief that film, a medium defined by combining video and audio, cannot function as an art form without both, and it shaped my views of the capabilities and limitations of cinema. In my mind, there was simply no way that Raiders of the Lost Ark would be a good film without audio or colour, it simply shouldn’t work; but it does. I’ll admit it, Soderbergh was right; by stripping away the original audio and colour of the film, the genius of Spielberg’s direction and Slocombe’s cinematography was apparent, and I would like to share my takeaways. What purpose does audio in film serve, how does the visual storytelling in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) enhance the viewing experience, and how can I apply it to my own work?

The Importance of Audio in Film

During my undergrad, one of the most informative lectures was an exercise you can try right now. Below is a clip from The Thing (1982), directed by John Carpenter. While you watch the edit, consider how clearly you understand the scene in each version.

Video Only:

Central conflict of the scene isn’t clear, reinforcing paranoia of the unknown but failing to convey the purpose of the scene visually.

Unable to convey the importance of MacReady’s torn clothing, why Windows lunged at Palmer, or Child’s refusal to open the door.

The wide shot of the group shows everyone in front of Nauls, but his closeup shows the crew surrounding him, a cheat to allow the audience to see the crew at all times.

Setting and space is clear, you understand where each character is because the blocking and movement is simple.

Audio Only:

Central conflict is clear, they openly discuss if MacReady is now a threat, the odds of his survival, and their uncertainty of opening the door.

Nauls clearly explains why MacReady’s torn clothing is important, and we learn he’s panicked because he cut the line, leaving MacReady to die.

The group’s agitation, distrust, and paranoia is clearer, but doesn’t indicate the group is aiming weapons at Naul.

Setting and space is unclear, diegetic audio isn’t conducive to understanding the scene’s space.

These points aren’t made to criticize Carpenter's direction, but to emphasize that, by visual storytelling alone, the audience cannot interpret the central conflict. The audio is used in addition to the visuals to fully convey the scene to the audience; it does not lean on the audio to save its storytelling, it uses it in conjunction with visuals. The Thing is a great movie, you'd be hard pressed to argue that John Carpenter can’t convey body horror and paranoia without audio, and I’ll concede that prior scenes provide context for this one, but the point remains. Carpenter masterfully uses both visuals and audio to convey the story with efficiency, but functionally speaking, the film fails when you separate video and audio from one another.

So why does Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) function so well in comparison without audio and in grayscale?

Visual Storytelling in Raiders of the Lost Ark

I encourage you once again to go to Soderbergh's blog (Link) and watch the scene from 2:54 to 3:45, as it’ll be our case study for analyzing the visual storytelling of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

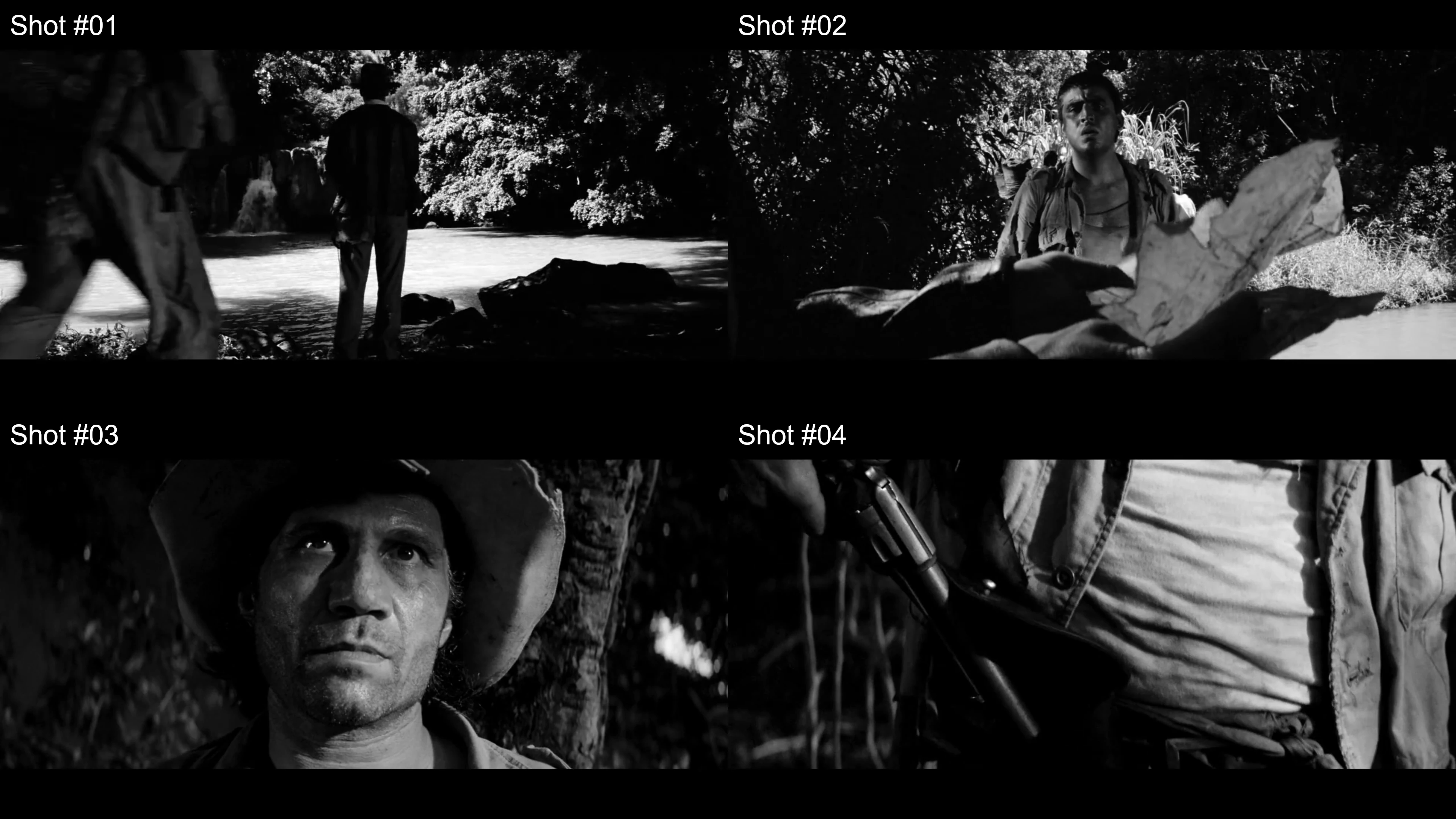

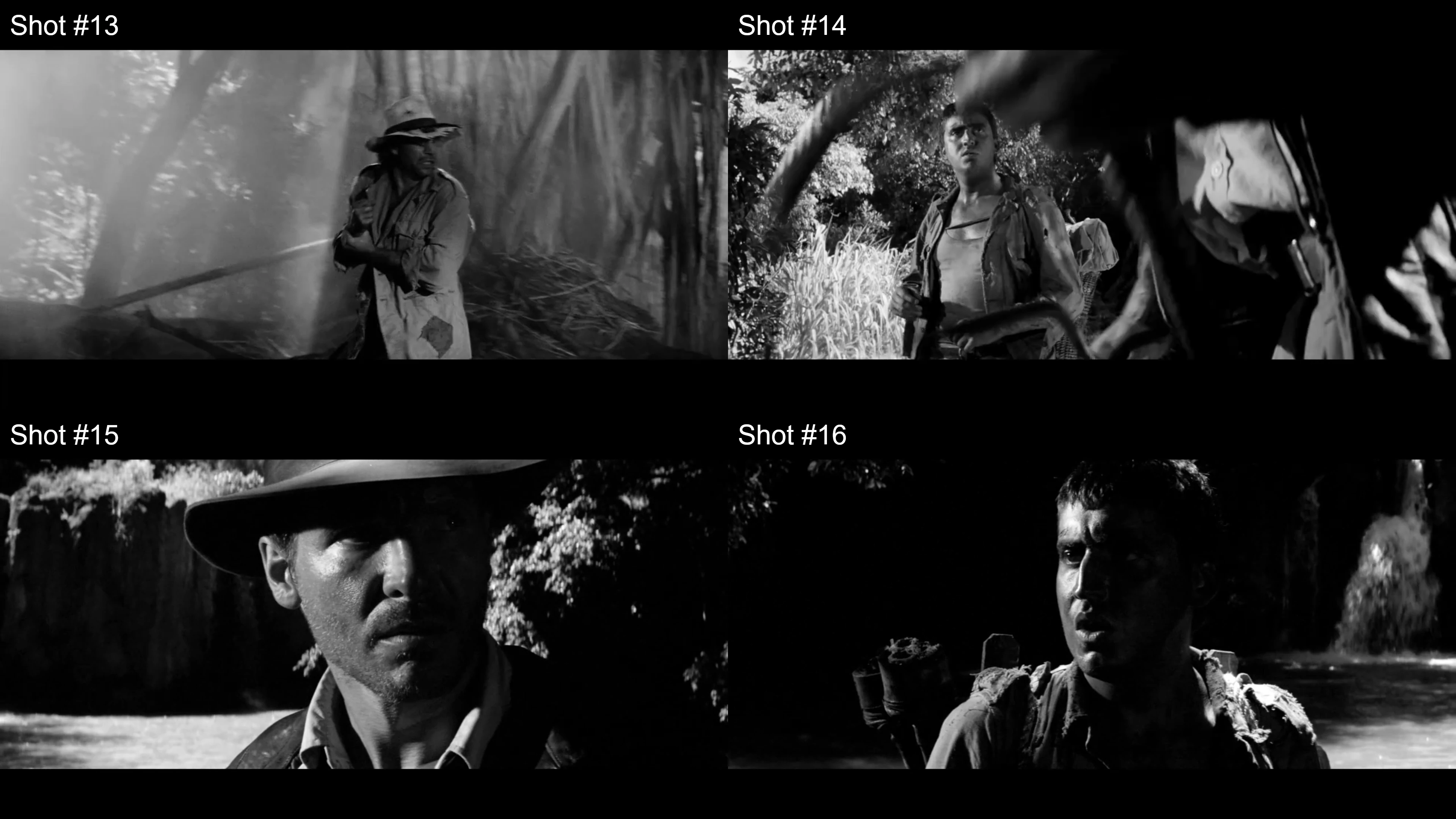

The above photos are a compilation of sixteen shots from the scene, which through a combination of Steven Spielberg's direction and Douglas Slocombe's cinematography, clearly conveys the scene's central conflict, staging, and action.

Spielberg’s Direction: Central Conflict, Characters, and Staging

As the scene begins, we see Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) walk up to the river's edge and hold out his hand for Satipo (Alfred Molina), who produces a map. While Indy is reading the map, Barranca (Vic Tablian) steps out from the bushes, and draws his revolver. This conveys each character's motive and role:

Indy is leading the expedition, and we can assume he organized it, a task which demands personal investment and determination.

Satipo stands at Indy's side, he’s a pack mule at his beck and call, and his agitation coupled with his obedience to Indy shows he's motivated by a promised reward.

Barranca slinks behind the group, his eyes darting between Indy and Satipo, indicating he is wary of the others, with the next shot telling us it's because he intends to betray them.

Within four shots, we're able to distinguish the central conflict of this scene; the group is hunting for something worth killing someone to obtain; and we understand what’s at stake for each character, allowing the next twelve shots to focus on the resolution.

These four shots also establish each character’s traits and emotions:

Indy’s stance and the way he holds out his hand for the map shows his professionalism and commanding presence, but likewise it shows he’s abrasive and practical.

Satipo’s expression and waiting for Indy show he's reliant on his skills, and probably naive to the true danger he finds himself in, but likewise his agitation shows he feels put upon.

Barranca’s stone cold expression and shifting eyes shows he’s calculating, but more importantly, he doesn’t reach for his gun until he thinks he has an opportune moment.

These traits fall under archetypes the audience is familiar with, and as such we quickly understand and assume Barranca will succeed in killing Indy. However, shot five shows a slight head turn from Indy; he’s aware of Barranca’s betrayal, and perhaps he even anticipated it. Within five shots, and before the duel even starts, the audience already knows who won. Barranca might be a cold-blooded killer who could bully Satipo, but Indy is more quick-witted and capable, hence why Barranca didn’t try to betray him until he had his back turned; he knew he’d lose in an honourable fight.

An underrated element of any good scene is character staging. Staging is the physical placement of characters in a scene, and as directors, it seems obvious in our mind’s eye where each character is in relation to one another, but that isn’t apparent to the audience. As such, the most important tool for efficient visual storytelling is translating a physical space to the audience’s perception.

Indy was the first person we saw approach the water, making him our central pole which the scene happens around.

Satipo walks up to Indy from the treeline, informing us of the distance from the camera/trees.

Satipo hands over the map on Indy’s right, walks behind Indy, and we see Satipo again in shot two on his left. As such, shot two is longer to give the audience time to reorient where Satipo is, and hides this length by focusing on the map in Indy’s hands.

Barranca steps out from the treeline, stares at Indy, darts to Satipo, and back to Indy, again reinforcing that Satipo is close to Indy’s left.

While it seems unnecessary to explain this, a common mistake for inexperienced directors is not establishing every character’s position relative to one another prior to the action. The audience is intelligent, and they will figure out the space as the scene progresses, but every second spent visualizing the space is time not spent enjoying the scene. By keeping Indy as a central pole which the characters move around, our cognitive load can shift to feeling what the characters feel; in other words, by efficiently translating the space, we efficiently tell the story.

Slocombe’s Cinematography: Composition, Lighting, and Editing

While clear direction and staging is the most valuable tool in communicating conflict and characters, the role of the cinematographer cannot be understated. Shots five to ten happen in the span of seconds, yet we’re able to follow the movements and actions of each character. This is done through several key choices, which are exemplified when shown in grayscale:

Indy remains in black silhouette on white backdrop at all times. His form is constant, and in addition to adding to his brooding and mysterious personality, it separates him from the evenly lit Satipo and Barranca.

Indy is always kept in or near the center of the frame. Shot 5 is Indy’s back from Barranca’s perspective, 7 is Indy’s hip, 8 shows his hand over his shoulder, 9 has Satipo in the background, and 10 has all three of them in frame, but Indy is always in the center. The audience doesn’t get lost from one cut to the next because the rule is always the same; Indiana Jones stays in the middle.

The characters (foreground) and the foliage (background) are never the same lighting level. This reinforces the scene’s tone, adding dramatic flair reminiscent of detective noir, but also ensures their movements aren’t obscured by darkness, making their actions easy to read.

Shot 12, Indy walks out from the darkness into the light, not vice versa, and finally reveals Indiana Jones to the audience. The shot could’ve started with him lit, but doing so would’ve caused confusion since he’s always been a dark silhouette; him walking into the light transitions him from silhouette to person.

Shots 9, 11, 13, 14, and 16 show us the reactions of the other characters. By showing Barranca’s fear and Satipo’s surprise instead of cutting away to Indy, it reinforces that what he just did was extraordinary; the most important element of any stunt is the reaction, because the reaction informs how effective an action was.

Barranca is shown in Shot 3 and 6 from low angle close-up, but once Indy disarms him, Shot 11 shows him neutral angle, and Shot 14 and 15 show Indiana Jones in low angle. Barranca starts the scene in control, he is the domineering force of this conflict, but once Indy disarms him, he takes his power away, putting him in control.

Shot 6 shows Barranca already aiming at Indy, Shot 7, 8, and 9 show Indy’s response, but Shot 10 shows Barranca still raising his gun. This subtle altering of time allows the audience to clearly see both of their actions, despite the duel actually happening at the same time.

These are just a few of the many things Slocombe’s cinematography accomplishes, and even in grayscale, his work ensures the entire film is readable and easy to follow, no matter how fast the cut and quick the action.

Applying Spielberg’s and Slocombe’s Techniques

After analyzing Raiders of the Lost Ark, it's important to remember that our takeaway isn’t that audio is useless. The key argument Soderbergh makes is that while all films should have sound, sound should be treated as a supplemental tool in the pursuit of storytelling, not as a crutch. A film's composition and staging alone should be strong enough to convey the story, and sound should provide details and context clues to further clarify what we see.

But why should we care whether or not our audio is the main driver of our storytelling? Simply put, our visual processing is much faster and more accurate than our auditory, and by concentrating 70-80% of our story into visual elements that can be quickly understood and followed (ie. show, don’t tell), we ensure our story is as efficient as possible.

I’m emphasizing the importance of efficient storytelling so heavily because storytelling is a costly process, both monetarily in film production, and emotionally for the audience. You’ll often hear the phrase ‘time is money’ when you’re on a film set, and while that’s quite literal for the production manager, it is mentally taxing for the audience to have to process and digest our stories, and every second wasted is attention lost. You probably have a story to tell that is compelling, interesting, and thought provoking, but it is a damned shame that far too many stories fall on deaf ears because it takes too long to tell itself.

One of the hardest things for me to learn was how to cut out work that unnecessarily added to my runtime; especially scenes I was personally invested in because I spent so long writing them. But the cutting room floor exists for this exact purpose, and the best method to prevent agonizing over lost media is planning in advance as to how you’ll convey the story visually. As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words, and hopefully this breakdown has inspired you to experiment with new forms of visual storytelling in your creative work.

Thank you so much for checking out my post! If you enjoyed this article, check out some of my other Blogs. At the top of this post, you can click Follow My Work to join my newsletter or follow my social media, or click Support My Work to share this post or donate $5!

Citations

Soderbergh, S. A. (2014, September 22). Raiders. Extension 765. February 10, 2024, https://extension765.com/blogs/soderblog/raiders

Universal Pictures. (1982). The Thing [Film]. United States.

Comentarios